Audio / Vision / Culture

11. & 12.07.2022 | Workshop by the Cinepoetics group with Hauke Lehmann, Enis Dinç, Özgür Çiçek, Regina Brückner, Nazlı Kilerci-Stevanović, and Jan-Hendrik Bakels.

Research Focus: Audiovisual Cultures

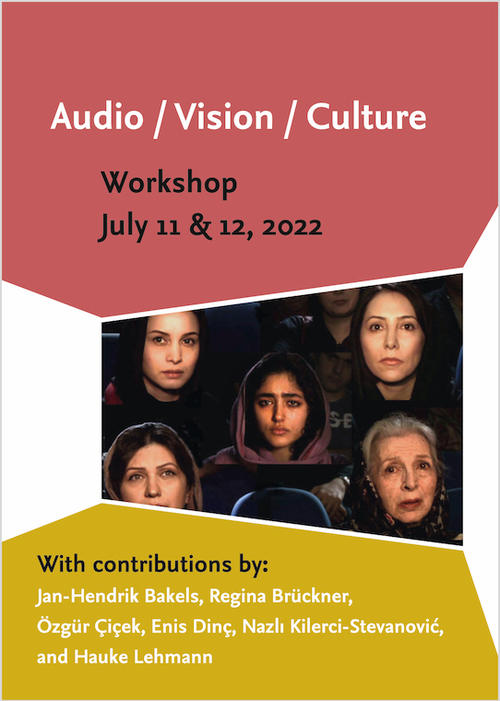

The group met on the first day of the workshop for a quick welcome session as well as a joint screening of Abbas Kiarostami's Shirin (IR 2008). This 2-day workshop focused on the dynamic intertwining that connects the cinematic image to music styles, movements of migration, technological developments, and political projects, and therefore is always related to processes of cultural community building.

The next day, Hauke Lehmann opened the first session with his work on "The Places of Sound. Audio, Vision, and Culture." He introduced culture as a dynamic oscillation between presence and absence. Lehmann noted that cinematic images construct an imaginary space off-screen, guide the perceiving activity of the audience, and in a more general sense feed off the cultural imaginary. With the example of Shirin, he explored the question of the relation of sound and images to onscreen and offscreen space. He argued that the film follows a strict division of sound and image, combines framing and montage to show a limited amount of people in the auditorium, employs different narrative devices, and presents different forms of non- or super-visuality.

Lehmann maintained that the film presented an abstract space that could neither be located in the image nor in the image the actresses look at. Instead, the images possess a metaphoric quality in the sense of a space hovering in between, of switching from one level of experience to another. Following his thoughts, the cinematic space is constructed here as a place where discourses of the past and of female spectatorship sediment themselves. This becomes especially apparent in the gestural quality of the (diegetic) audience's faces. In actualizing the conventional gestures of film viewing, the faces translate the invisible and spell out the affective dramaturgy. Audiovisual cultures are thus in general made up of such practices of translation.

In the second presentation of the day, "Sultan's Fear of the Cinema," Enis Dinç conducted a historical account of the arrival of cinema in the Ottoman empire. When the cinématographe arrived in Istanbul in 1896, fears of electrical fires caused by the projection lamp circulated and made a permit for screenings difficult to obtain. As women and men were segregated in public spaces, the cinema’s joint spectatorship was deemed morally reprehensible by Sultan Abdülhamid II. Film screenings and advertisements were thus strictly controlled, and politically and religiously sensitive images were not allowed. The Sultan even attempted to censor films in foreign countries which portrayed the Ottoman empire in an unfavorable light.

However, the Ottoman court was Western-oriented, and film screenings soon became part of the entertainment programs in the palace. Over time, the Sultan viewed cinema as a source of revenue for financing projects like the construction of railways. It was furthermore used as by him as a medium for propaganda. While it was first rigidly controlled in public, cinema culture in the Ottoman Empire was not prevented entirely, but rather developed specific (and controlled) conditions.

In her talk, "The Acoustics of the Past in Özcal Alper's future lasts forever (2011)," Özgür Çiçek focused on oral culture in Kurdistan as well as the use of sound and voice in Kurdish cinema. Her example, future lasts forever, presents testimonies and an unrevealed history of lived crises in everyday ordinariness. The use of telling multiple unrevealed personal histories in this film, argued Çiçek, is a practice that creates a multivocal narrative. This produces a state of being historical in the present, with a past that mediates itself through sound.

Çiçek then pointed out the different uses of the sound recordings in the film. The use of flashbacks creats a sense of continuous abandonment, and the film contrasts oral stories spoken in various local languages with the audiovisual stories spoken in mostly Western languages. The film's recordings of street sounds are described by Çiçek as random and disembodied testimonies of undocumented losses. Furthermore, the film at times takes on a documentary value when it positions a character and thus the audience as the listener. The listener gets involved in the creation of knowledge by listening to traumatic events and memories. Çiçek closed with a short exploration of the notion of recording as touching: recording someone is a practice based on trust, she explained, as one enters into an agreement with another.

The last of four presentations was held by Regina Brückner and Nazlı Kilerci-Stevanović. Their joint talk "The Sounds of Familiarity: On the Affective Potential of Popular Music in Film" began with a close reading of a scene in Fatih Akin's gegen die wand (DE 2004). Kilerci-Stevanović explained its pace, rhythm, and atmosphere in regard to a the popular Turkish song "Yine Mi Çiçek" by Sezen Aksu. The images of food and cooking, combined with the music, evoke a nostalgic feeling of togetherness, hapticity, and tenderness. However, the mood abruptly shifts to a tragic mode with an unexpected interruption. This, according to Kilerci-Stevanović, underlined the existence of contrasting feelings at the Raki table. The images merge with one's recollection of the past and even with memories that aren’t necessarily one's own, with both tied together by the joy of an incoming melancholy.

In the second part of the presentation, Regina Brückner focused on Thomas Heise's film stau – jetzt geht's los (1992), which she described as a film between a mythologized past and an indeterminate future, where violence lingers between buildings and the urban landscape. Brückner's close reading of a scene revealed a transition from one German popular song to another, all of which are commonly associated with the mixture of aggression and fun of football fans or drunken groups. The film contectualizes these associations to Neonazism in the early 1990s and East German Plattenbau-architecture. However, the film does not address a community of taste in the positive sense: While the songs are deeply anchored in German culture, they are linked to disgust and dissent.

In response to the talks, Jan-Hendrik Bakels presented four theses on audiovision in cinema: First, that there is no sound and vision in cinema, only audiovision in the sense of one Gestalt within which we differentiate; second, that the audiovisual whole is polyphonic; third, that from the embodied perception complex experiences of rising and falling tensions can be derived which shape dynamics of physiological affects in the spectators; and finally, that meaning-making is grounded in and derives from audiovisual dynamics.

Addressing Lehmann's presentation, Bakels noted that in shirin the spectators react to faces reacting to images and sounds. However, the audiovisual whole demands that we divide the different dimensions, which later becomes the space for interplay. Relating to Dinç's talk, Bakels mentioned the phenomenological thinking on audiovision and especially the paradigm of nonvisibility of the Sultan. Bakels then addressed Çiçeks presentation, noting that the multilayered temporalities are not generated by sound and image combinations, but only get realized in the experience of the spectator. Trauma gets constructed as a scattered, fragmented, and haunting present. Relating to Kilerci-Stepanović and Brückner’s talk, Bakels mentioned that while popular music takes us to the past, there is a difference between the experience of it in cinema and in daily life. Music in films is rather incorporated than received.

The closing discussion revolved around the integrity of the idea of an audiovisual whole while reactions to it differ. It also addressed the inadequacy of viewing subcultures in a binary way, the false idea of wholeness within modernity's history, the notion of culture as a conflict in meaning, and blending as the creation of something new by constant negotiation of sound and image in cinema.